Three years ago, in search of an affordable short-term rental in Paris, my husband and I wound up in the Denfert-Rochereau neighborhood, situated on the Left Bank, in the southwestern part of the city. It was a case of neophyte’s luck. Our Airbnb flat turned out to be a bit of a dump, but when terrorists struck several days after we moved in, on November 13, 2015, we were safely ensconced in an architectural gem. Called Villa Adrienne, it consists of 21 low-rise apartment buildings and freestanding houses behind a gate along Avenue du Général Leclerc that encloses a private garden.

In French the word villa is used to describe a mansion, but in this context it meant something else: garden homes or enclaves within the city, situated along a narrow alley or behind a gate. I would later come across mentions of about two dozen others in the city’s 20 municipal districts, known as arrondissements. Many of them are identified in Quiet Corners of Paris, a highly informative little 2006 book by Jean-Christophe Napias, a Paris-based journalist and author. Napias calls Villa Adrienne “one of the stars” of the 14th arrondissement.

Even the houses in Villa Adrienne had lofty names, in homage to poets, artists and philosophers. Ours was La Fontaine, after Jean de La Fontaine, the 17th-century poet and fabulist. Typical of those around the rectangular-shaped garden, it was a four-story yellow-brick walk-up, with an Art Nouveau glass awning on its front. Adjacent to it was a two-story limestone structure, with shutters and a dormer that seemed to date to an earlier period, and an attached extension that looked like it might once have been a stable. On the villa map posted outside the concierge office, it was labeled La Petite Chocolatière (the little chocolate factory). Today it houses a branch of Jacadi, an upscale children’s clothing store that fronts on the boulevard.

A row of private homes extending back from La Petite Chocolatière was marked with the names of their current owners and, in some cases, their provenance. One Federal-style house, for example, built in 1948, had a plaque on the side, indicating that Carl Walter Liner, the Swiss painter, who died in 1997, lived there during the final years of his life.

Residents of Villa Adrienne, like those of the neighborhood, ranged from families with young children to elderly folks who may have lived at this address for many decades. If they minded transients like us, they certainly didn’t show it. As we approached the locked iron gate on Avenue du Général Leclerc, we occasionally found ourselves behind them. Everyone smiled and said bonjour, and motioned for the other person to enter first. Sometimes there were so many exchanges of après vous (after you) that the gate, which worked on an automatic mechanism, started to slowly swing shut.

Outside those gates, we fell in love with the neighborhood. So much so, that last year, while living in another (again dumpy) flat, at the edge of the more popular Marais section, we commuted back to the 14th arrondissement one Friday, just to go food shopping.

This year we returned for a two-week stay. Unable to find a rental at Villa Adrienne (there are very few), we secured an apartment just one block away, on rue Ernest Cresson – one of the quaint side streets that run perpendicular to Avenue du Général Leclerc. When the owner greeted us at check-in and we mentioned where we had lived previously, she looked at us wistfully. “It’s very hard to find an apartment in Paris,” she said. And she, too, would have preferred Villa Adrienne.

Still, we could experience the daily rhythms of this part of Paris: parents rushing children off to school in the morning; early-evening chatter at the cafés; and wonderful food shopping all around us. Within a five-minute walk of where we had previously lived, down rue Mouton-Duvernet or rue Brézin, we had our pick of boulangeries and restaurants, a couple of butcher shops, a fish store and a fromagerie (cheese shop). Just a few minutes’ walk west of there, toward Avenue Denfert-Rochereau, was a pedestrian-only street on rue Daguerre, with an assortment of specialty food stores and restaurants.

Indulging my inner sweet tooth at Désiré Pâtisserie-Chocolatier, I ate my way through their display case of classic French pastries.

By the end of our latest stay, we had some new favorites. Boucherie Hugo Desnoyer (45 rue Boulard) was my preferred source for the veal scallops that I prepared with mushrooms and cream sauce. Indulging my inner sweet tooth at Désiré Pâtisserie-Chocolatier (7 rue Brézin), I ate my way through their display case of classic French pastries. And by the second week of our stay, as I ordered my bread at the busy Moisan boulangerie (4 Avenue du Général Leclerc), the previously somewhat sour saleswoman smiled at me and said, “À demain.” (See you tomorrow.)

The trade-off for experiencing this slice of Parisian life in an outer arrondissement is that one spends more time in transit to most tourist attractions. But by using one transportation system or another, we could get almost anywhere in the city in half an hour or less. We were also just a few Métro stops from such popular destinations as the Luxembourg Gardens and three legendary Montparnasse cafés that Ernest Hemingway used to frequent – La Closerie des Lilas, La Rotonde and Le Dôme.

Back in our neighborhood, after a day of activity, we seldom saw any other tourists, with one exception: In line to visit the Paris Catacombs. The Denfert-Rochereau Métro station is across the street. Although it was empty when we visited in 2015, a few days after the terrorist attacks, that isn’t the norm. Admission is limited to 200 people at a time, and it’s not unusual for there to be a wait of an hour or more.

Situated up to 82 feet underground, this is an eerie place, where water drips from the ceiling, as rows of skulls, interspersed in stacks of shinbones, stare out at visitors. But this oddly poetic subterranean museum also offers a fascinating piece of Paris history.

Many centuries newer than its counterpart in Rome, the Paris Catacombs were developed in the late 18th century to address an urban-planning challenge. The macabre concept was to close many of the city’s overcrowded and overflowing cemeteries, which had become a public health threat. Their contents would be exhumed and deposited into abandoned quarries where limestone building materials had been excavated from the subsoil in what were then the Paris suburbs.

The process began in 1786 with the Cimetière des Saints-Innocents, which had been a site of mass graves since the Middle Ages. Through a series of exhumations over a period of 15 months, the remains of 2 million Parisians were removed from that cemetery alone. The process continued as 16 more cemeteries, many adjacent to churches, were eliminated between 1792 and 1814. The Catacombs were enlarged from 1859 to 1860, to make room for the contents of additional cemeteries unearthed during the rebuilding of Paris, overseen by Georges-Eugène Haussmann, Emperor Napoléon III’s head of public works. By then the Catacombs held 6 million human remains, most of them moved from other burial grounds. Only in several cases of mass carnage, all during the French Revolution, were people directly buried in the Catacombs.

Today one enters through an unassuming façade, painted green, to the left of one of two identical buildings on either side of Avenue du Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy. Though called the Barrière d’Enfer (Gate of Hell), these 18th-century buildings are unrelated to the Catacombs. They were once tollhouses used to deter tax evaders.

Underground, the old street names are inscribed as directional signals at various junctures; evidence of quarrying techniques, which created supporting pillars and stone walls to avoid structural collapse; and initials of various quarry inspectors on the walls.

Not for the physically infirm or claustrophobic, a Catacombs tour requires visitors to descend 131 steps at the entrance, climb 83 steps back up to the exit, and in between walk 1.4 miles along a circuitous route that is nearly the distance between three Métro stops. Admission costs €13 (about $14.75 at current conversion rates). The excellent audio tour will set you back another €5 ($5.67).

Even with some historical background, the décor is hard to stomach: stacks of bones and skulls, mostly arranged symmetrically, and in one spot skulls positioned in the shape of a heart. For all the dignity and respect the Catacombs exude – stacks of bones are labeled by cemetery and year they were exhumed – there is something terribly ghoulish about art constructed with human remains. Threading through room after room of it is both creepy and humbling.

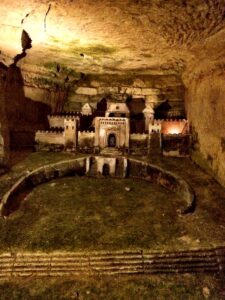

In the Paris Catacombs, an 18th-century quarryman crafted this sculpture of the Port Mahon citadel.

For me, one of the most moving sections of the Catacombs had nothing to do with its original purpose but with one man’s creative impulse: an elaborate sculpture of the Port Mahon citadel carved into the Catacombs’ limestone walls. This was the handiwork of an 18th-century quarryman known officially only by his last name, Décure. As a member of Louis XV’s armies, he is believed to have been imprisoned by the British on Minorca, one of Spain’s Balearic Islands. Later, as a quarryman in Paris, his co-workers nicknamed him “Beauséjour” (beautiful sojourn), as they observed him craft this detailed sculpture from what he apparently recalled as paradise.

From a distance, it looks like a giant sand castle, but up close one can see individual buildings in the town and black flint-stone tiles that represent the sea. After working on this labor of love from 1777 to 1782, Décure was constructing a staircase to access it, when he was killed by the collapse of a quarry roof.

Elsewhere in the Catacombs’ dark and gloomy depths, I paused to read the poetry or brief quotations posted next to many bone stacks. Not surprisingly, a good number deal with the frailty or brevity of life. Most chilling, in the wake of the 2015 massacre, was the unattributed turn of phrase, “Pensez le matin que vous n’irez peutêtre pas jusqu’au soir et au soir que vous n’irez peut-être pas jusqu’au matin.” Think in the morning that you will not exist until the night and in the night that you will not exist until the morning.

Beneath the bustling streets of 21st-century Paris and the neighborhood that I find so captivating, is a reminder to make every day count.

Deborah L. Jacobs is the author most recently of the five-time award winning book, Four Seasons in a Day: Travel, Transitions and Letting Go of the Place We Call Home, about her adventures – and misadventures – living in France. Follow her on Twitter at @djworking and join her on Facebook here. You can subscribe to future blog posts by using the sign-up box on her website’s homepage.

RELATED POSTS

Where to Buy Kitchenware in France

Three Paris Markets That Are Worth the Journey

Behind a gate along a busy Parisian boulevard, Villa Adrienne consists of 21 low-rise apartment buildings and freestanding houses that share

a private garden.

Behind a gate along a busy Parisian boulevard, Villa Adrienne consists of 21 low-rise apartment buildings and freestanding houses that share

a private garden.

“Quiet Corners of Paris” is my favorite book about unique spots in the city I adore. We carried it with us on our recent trip and enjoyed visiting some of the villas mentioned therein.

Yes, it is a wonderful book. I only wish it was available in a digital edition: It was too heavy for us to carry on a three-month sojourn that ended in Paris.