It’s cold, damp and dark in Paris at this time of year. And there’s only so much warming up you can do by sipping hot chocolate under the heat lamps at a café or stuffing piping-hot roasted chestnuts purchased from a sidewalk vendor into your pockets.

During two recent weeks in the City of Light, I visited four extraordinary art exhibits that take the chill off winter. All are open just for a limited time, and will not go on tour. Together they’re enough to give art buffs a reason to bundle up in one of those blanket scarves that the French are so deft at tying and seize the day.

Gustav Klimt at the Atelier des Lumières, 38 rue Saint Maur. This new digital museum, housed in a 19th-century iron foundry that has been turned into a culture space, is devoted to immersive art. This is art that envelops us as viewers and dominates our senses. Couple modern technology with an inaugural exhibit devoted to the Viennese artist Gustav Klimt, who’s been dead for 100 years, and what do you get? An audiovisual experience that seems to lift us inside Klimt’s gaudy decorative paintings.

You don’t have to be a Klimt fan to love it; as it happens, there’s not a painting in sight. Instead, this exhibit relies on computer graphics and video animation to create a high-definition blend of Klimt’s portraits, landscapes and nudes (think The Kiss and Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer). Set to music, it’s projected on all the concrete surfaces of the old foundry, including the ceiling and floor.

This exhibit, plus two shorter ones (one featuring Viennese artists Egon Schiele and Friedensreich Hundertwasser, whom Klimt influenced; and a contemporary work on color), last about an hour. Most people enter in the middle of the cycle, which is a bit disorienting – like walking into a movie in progress. The inclination, then, is to find a place to sit, on one of the few benches or industrial spools available for the purpose; or even to plunk down on the floor.

Once you’re adjusted to the dark, standing or strolling around (even climbing the stairs to the balcony) heightens the kaleidoscopic sensation and makes us feel like we are walking through the art itself. Adults will find this in sharp contrast to the more familiar experience of viewing paintings on the wall of a museum or gallery. But children, who don’t have that frame of reference, take to it very naturally: They can be seen swirling and dancing in the shadows, to my amusement and the obvious annoyance of some adult visitors.

The exhibit, extended until January 6, tends to sell out on weekends, when you can only book online (as is also true from December 22 to January 6). To secure a spot and avoid queuing, reserve tickets in advance. Another way to beat the crowds is to arrive on a weekday shortly after the museum opens, at 10:00. Figure you’ll be done in time for lunch at one of the reasonably priced ethnic restaurants in the neighborhood. The South Indian Thali lunch at Madoura (1 rue Guillaume Bertrand) is delicious and an €8 bargain (about $9 at current conversion rates). On the day that my husband and I lunched there, the restaurant was filled with office workers.

Joan Miró’s 1922 painting, “La Ferme,” was purchased by Ernest Hemingway.

Joan Miró at the Grand Palais, 3 Avenue du Général Eisenhower. Built for the Universal Exhibition in 1900, this enormous structure just off the Avenue des Champs-Élysées provides the perfect venue for massive, ambitious retrospectives. There, until February 4, is one devoted to the life and work of Joan Miró. It’s a rare opportunity to contemplate the artist’s career path and to see 150 examples of his work on loan from all over the world. Together they show how history and other artists influenced Miró, and how his style evolved, from early 20th-century avant-garde to surrealism.

One of the highlights from Miró’s detailist stage is the 1922 painting The Farm. It depicts his family’s farm in Montroig, to which Miró was very attached. In exquisite detail, the work, which measures about 56” by 49” and took Miró nine months to complete, shows the Catalan landscape, farmhouse and animals.

This painting, on loan from the National Gallery of Art, in Washington, D.C., had a stormy and storied provenance, not recounted in the Grand Palais audioguide. It was acquired by Ernest Hemingway in 1925 for $3,500 francs ($175 in those days) – a sum he could not at the time afford. According to his biographer Michael Reynolds, Hemingway passed it off as a birthday gift to Hadley Richardson, his first wife, and used her trust fund money to pay for it. Initially it hung over the bed in their Paris apartment. When they divorced, Hadley got the painting, but then lost possession after lending it for an exhibit. A plot, thicker than that of most Hemingway novels, ensued, as a recent article in Vanity Fair reports.

During the summer of 1936, Miró retreated to Montroig and produced a very different kind of art. Reacting to the Spanish Civil War and the rise of fascism, he created 27 identically sized works on raw Masonite. Combining streaks of paint with plaster, tar and gravel, they are a graphic expression of his horror.

His 23 Constellations, done between 1939 and 1941, are much more lighthearted. In their simplicity, they, too, are a reaction to a shortage of materials caused by war. But the dream-like pictograms they contain became a hallmark of Miró’s later, surrealist, work. The resemblance to the oeuvre of the American artist Alexander Calder is no coincidence: They met in Paris in 1928 and became close friends.

Mutual admiration between Miró and Picasso is also represented in this exhibit. It includes a 1919 self-portrait of Miró from the waist up, wearing a Catalan peasant’s jacket. According to the audioguide commentary, “Miró’s gallery owner gave it to Picasso, who liked it so much he kept it all his life.” It was donated by his heirs to the Musée National Picasso-Paris. Miró, who was working on an abstract painting of a female bird when Picasso died in 1973, named the work Hommage à Pablo Picasso. Today it’s owned by the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid.

Those who can’t get to Paris before the exhibit closes can take a digital tour covering 35 of the works displayed using the Grand Palais app. Once you have downloaded the app from the Apple Store, the Miró guide is available as a free in-app download. If you want to brush up on your French (or don’t speak the language), you can follow the audio by reading the English commentary on your mobile device beneath each work represented.

Like father: La Balançoire, 1876, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Renoir Father and Son at the Musée d’Orsay, 1, rue de la Légion d’Honneur. If there were a prize for creative curation, I would give it to this exhibit. It tackles a difficult subject: common themes in the works of Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir and his son, the master filmmaker Jean Renoir.

First shown at the Barnes Foundation, in Philadelphia, which owns the world’s largest collection of paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, this exhibit is at Musée d’Orsay until January 27. It’s the result of a collaboration between the two institutions and Cinémathèque Française. (The show’s curator, Sylvie Patry, a deputy director at the Musée d’Orsay, previously worked at the Barnes.)

Without explicitly probing into the psychological depths of the father-son attachment, this multimedia exhibit presents their reciprocal influences in visual terms, and the relationship between painting and film. In addition to paintings, it includes film clips, ceramics, photographs, costumes, posters, drawings and documents.

Like son: The actress Sylvia Bataille in a scene from Jean Renoir’s 1936 film, “A Day in the Country.”

No surprise that father and son favored some of the same locations: the River Seine, Montmartre and southern France. To illustrate, Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s The Swing (1876) is juxtaposed against Jean Renoir’s film A Day in the Country (1936), which contains a similar scene filmed outdoors. That film is an adaptation of Guy de Maupassant’s short story “Une Partie de Campagne.”

If the father was a model for the son, the converse was also true. The exhibit contains six paintings of Jean as a child. In one, dated 1903, when Jean would have been about seven, he could be mistaken for a girl, because his father had not yet allowed his hair to be cut. Andrée Heuschling, the painter’s last model, became Jean’s first wife and played the character Catherine Hessling in his silent films.

Jean was 26 when his father died, in 1919, and as the museum audioguide indicates, sold many paintings inherited from his father to finance his film career. He later spent 20 years writing the biography, Renoir, My Father, published in 1962. This exhibit fuels our curiosity about their obviously complicated relationship.

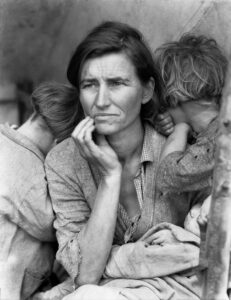

Dorothea Lange at the Jeu de Paume, 1 Place de la Concorde. While many visitors to Paris are eager to see Leonardo da Vinci’s painting the Mona Lisa at the Louvre Museum, until January 27 they can also view an image of the woman once dubbed “the Mona Lisa of the Dust Bowl.” It’s a photograph of Florence Owens Thompson, the migrant mother of five, snapped by Dorothea Lange in 1936 when she documented the plight of pea-pickers in Nipomo, California during the Great Depression. This photo, titled “Migrant Mother,” is part of “Politics of Seeing” – a blockbuster retrospective of the photographer’s work currently at the Jeu de Paume.

Dorothea Lange at the Jeu de Paume, 1 Place de la Concorde. While many visitors to Paris are eager to see Leonardo da Vinci’s painting the Mona Lisa at the Louvre Museum, until January 27 they can also view an image of the woman once dubbed “the Mona Lisa of the Dust Bowl.” It’s a photograph of Florence Owens Thompson, the migrant mother of five, snapped by Dorothea Lange in 1936 when she documented the plight of pea-pickers in Nipomo, California during the Great Depression. This photo, titled “Migrant Mother,” is part of “Politics of Seeing” – a blockbuster retrospective of the photographer’s work currently at the Jeu de Paume.

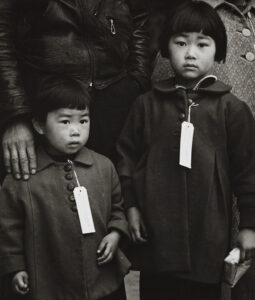

Most of the work in the Jeu de Paume exhibit was done while Lange was a documentary photographer for various U.S. government agencies, making her close connection with her subjects that much more remarkable. Commissioned by the War Relocation Authority to cover the internment of American citizens of Japanese descent in 1942, Lange produced photos so haunting that they ran at cross-purposes with government propaganda. The government, concerned about the potential backlash they might elicit, impounded the photos and did not release them for publication until 64 years later. A number of them, including one of children required to wear tags, are included in this exhibit.

Most of the work in the Jeu de Paume exhibit was done while Lange was a documentary photographer for various U.S. government agencies, making her close connection with her subjects that much more remarkable. Commissioned by the War Relocation Authority to cover the internment of American citizens of Japanese descent in 1942, Lange produced photos so haunting that they ran at cross-purposes with government propaganda. The government, concerned about the potential backlash they might elicit, impounded the photos and did not release them for publication until 64 years later. A number of them, including one of children required to wear tags, are included in this exhibit.

At its best art moves us not just while we are at a museum, but also expands our horizons long after we have departed. Such was the case with several of these exhibits. My consciousness raised about the work of Jean Renoir, I’m inspired to rent his epic films Grand Illusion (1937) and The Rules of the Game (1939). They weren’t featured in the exhibit because they did not fit with its theme.

Back home in Brooklyn, New York, I have on my nightstand Linda Gordon’s book Dorothea Lange: A Life Beyond Limits; The Necklace and Other Stories: Maupassant for Modern Times (an anthology that includes “A Day in the Country”); and Joan Miró: Selected Writings and Interviews, edited by Margit Rowell.

While I borrowed the first two from my local library, the latter was already on my shelf – apparently an impulse purchase when I visited the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona. My entry ticket from seven years ago marks my place. Now I have a new incentive to finish that book.

Deborah L. Jacobs is the author most recently of the five-time award winning book, Four Seasons in a Day: Travel, Transitions and Letting Go of the Place We Call Home, about her adventures – and misadventures – living in France. Follow her on Twitter at @djworking and join her on Facebook here. You can subscribe to future blog posts by using the sign-up box on her website’s homepage.

RELATED POSTS

Four Great Rooftop Views of Paris

An immersive exhibit at Atelier des Lumières, featuring Gustav Klimt, envelops viewers. © Culturespaces / Eric Spiller

An immersive exhibit at Atelier des Lumières, featuring Gustav Klimt, envelops viewers. © Culturespaces / Eric Spiller