If politics and the pandemic have prompted a flurry of new books, the horrifying twist of events has also inspired readers to prune their shelves. By the seventh month of living and working in virtual isolation, subjects that once held our attention seem passé or absurdly irrelevant.

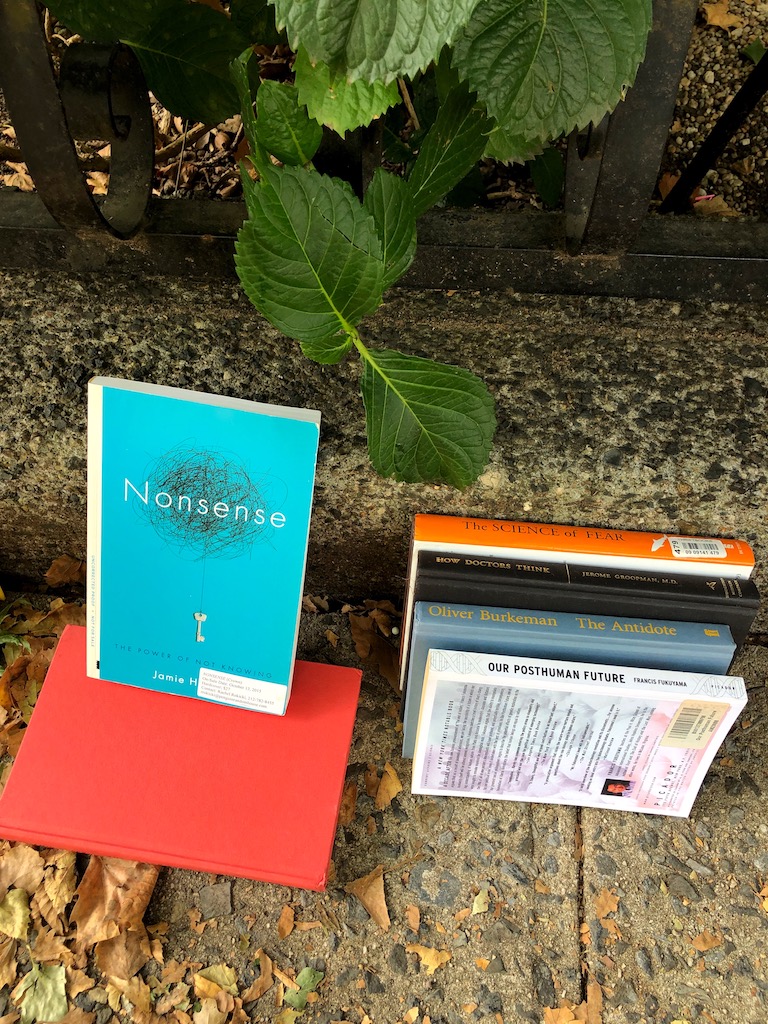

During a three-mile walk through several Brooklyn neighborhoods last weekend, the unwanted volumes formed an autumn montage against the urban architecture and fallen leaves. It’s a tradition around here to give away books by putting them out on the stoop, or along the fence in front of a building. Someone with an eye for irony displayed Nonsense: The Power of Not Knowing, by Jamie Holmes, beside a stack of books, spines up, with these titles: The Science of Fear; How Doctors Think; The Antidote; and Our Posthuman Future.

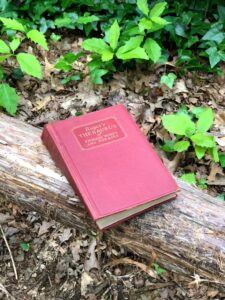

Over the years I’ve made valuable additions to my cookbook collection from volumes discarded in a similar fashion, but most of what I have seen since the start of the pandemic has been an array of titles that even a book junky like me wouldn’t want. A copy of Roget’s Thesaurus, abandoned on a log in Prospect Park in May, left me wondering if its owner had gotten fed up after an unproductive search for a synonym for “pandemic.” Down the block, someone with an obvious penchant for travel put out an enormous bag in July, brimming with guidebooks. And in front of the Eileen Fisher store on Bergen Street last weekend, a copy of Debating the Death Penalty: Should America Have Capital Punishment? got no more than a fleeting glance. As an author, I can’t think of a worse insult.

A friend kept me company during my recent walk, from a socially safe distance of 2,831 miles. Since May I’d been comparing notes about literary discards with Wendy S. Goffe, a trusts and estates lawyer with Stoel Rives in Seattle. Goffe, who browses at Little Free Library exchanges and on a Facebook “buy nothing” group, had observed an uptick in unclaimed self-help books. When it comes to succeeding in the workplace, in particular, “people have definitely reached the ‘screw it’ stage,” she said in an e-mail. In contrast, “there is a noticeable shortage of beach/chick lit. People are hoarding that. Me included.”

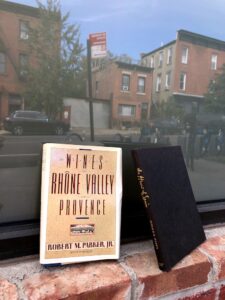

En route last weekend, I sent her photos of some tempting finds: Robert M. Parker, Jr.’s Wines of the Rhône Valley and Provence; and The Heart of Spain, by Donald B. Harris, inscribed by the author “to Moe and Joe.”

“That counts as self-help in these desperate times,” said Goffe, encouraging me to snag these hardcovers. But alas, I was headed to Trader Joe’s on foot, and could not tote the volumes along with the many pounds of granola ingredients that I had planned to purchase. Her subsequent advice, “Surely you could have carried Stumbling on Happiness,” referring to a slender paperback by Daniel Gilbert that I spied at another location, landed too late for me to act on it. I had a twinge of urban forager’s remorse.

When New York shut down, in March, I saw an opportunity to savor the unread books on my own shelves. It’s an opportunity that I have not seized. Mind you, I really do intend to read three volumes of Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past; two collections of short stories from The New Yorker, compiled (respectively) for the magazine’s 15th and 25th anniversaries; and Eleven Plays of Henrik Ibsen, with an introduction by H.L. Mencken. It just hasn’t happened yet.

If anything positive results from my recent stroll, it might be the motivation to purge some less treasured volumes from my shelves. On the rainy Monday that followed, I pulled up a ladder.

It happened to be the first day of the Senate Judiciary Committee hearings, on the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court. And that seemed like an auspicious moment to discard The Cinderella Complex: Women’s Hidden Fear of Independence (1981), by Colette Dowling; Games Mother Never Taught You: Corporate Gamesmanship for Women (1977), by Betty Lehan Harragan; and My Mother My Self (1977), by Nancy Friday.

Down, too, came five books about sexual harassment that preceded the #MeToo movement by 20 or so years. The most ironically titled was published in 1992, edited by two male attorneys – Martin Eskenazi and David Gallen – and called Sexual Harassment: Know Your Rights! That exclamation point is theirs (or their editors’), not mine.

Other discards required me to confront the realization that, pandemic or not, some chapters in my life have ended. Now that my son is 23, I no longer need an assortment of books about travel with children. Nor do I have any further use for the career advice contained in such onetime bestsellers as The One Minute Manager (1982), by Kenneth Blanchard and Spencer Johnson; What They Don’t Teach You at Harvard Business School: Notes from a Street-Smart Executive (1984), by Mark H. McCormack; or The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People: Powerful Lessons in Personal Change (1989), by Stephen R. Covey. No doubt all were acquired with the best intentions, but, for better or worse, none have been well thumbed.

Six shelves into my purge, I had already packed a giant bag from one of many Fresh Direct grocery deliveries received during the pandemic. Emblazoned with bright orange peaches, the bag bears the logo, “Life is peachy.” Somehow it seems as hopelessly out-of-date as the books that now fill it.

Deborah L. Jacobs, a lawyer and journalist, is the author of Four Seasons in a Day: Travel, Transitions and Letting Go of the Place We Call Home and Estate Planning Smarts: A Practical, User-Friendly, Action-Oriented Guide.

RELATED ARTICLES

Why This Professor Is Writing Letters for People Feeling Blue

Pandemic Pursuit: A Yearbook Lost and Found

In Brooklyn, New York, discarded volumes form an autumn montage against the urban architecture and fallen leaves.

In Brooklyn, New York, discarded volumes form an autumn montage against the urban architecture and fallen leaves.