Three years ago I worked in a high-tech sweatshop. At The Content Mill, as I will call it, data on my blog traffic was updated every 15 minutes. Management used metrics to express monthly performance goals. Though I far exceeded them, nothing was ever enough. On the cusp of holidays, like the upcoming Labor Day weekend, the head honcho routinely sent a midmorning e-mail to the entire editorial staff, complaining that too few of us had put up new content that day.

I loved being a writer and had hoped to stay in that position until I was in my mid-60s, or older. But on many days, my role, covering personal finance for baby boomers, reminded me of the I Love Lucy episode in which Lucy gets a job in a chocolate factory. In one hilarious scene, Lucy and her friend Ethel stuff chocolates into their mouths, under their hats and down their dresses, when they can’t keep up the pace of wrapping candy as it comes off the conveyor belt.

In my case there was nothing to laugh about, though. Job stress was taking such a heavy toll on me that I was on the verge of burnout.

Like a bad dream that eventually passes, that mostly miserable experience is fading into a distant memory. Today my husband, Ken, and I divide our time between New York and France, with me working from wherever we happen to be. My latest book, Four Seasons in a Day: Travel, Transitions and Letting Go of the Place We Call Home, about living in a foreign country and how we created (and financed) this new lifestyle, was published in May. An audiobook version, performed by Tavia Gilbert, has just been released.

After a three-year hiatus, I’m also excited to get back to blogging, but on very different terms. Instead of churning through The Content Mill, these articles will be published right here, on my own platform. With no pressure to generate “clicks,” I can focus on my most important goals as a journalist: to inspire, inform and entertain. This article is the first of what I expect will be three or four blog posts per month.

So it seems appropriate to start by addressing one of the deepest fears of people who are stuck in oppressive, dead-end jobs, aren’t thriving within an organization, or have recently left a job by choice or circumstance. Often our first concern is about losing a steady paycheck and what it will cost for health insurance. Another issue for many people is what they will do when they get up in the morning. Without the structure of a job, they ask, “How will I find purpose and meaning in life?”

I get this question a lot, from people of all ages. And though I don’t think the anxiety is gender-specific, women may feel it most profoundly. There are still far too few of us in the upper echelons of most organizations. Therefore, we have a harder time envisioning ourselves as the boss – even of ourselves.

The answer, for both genders, lies in our human capital. I use this term to describe the skills and experiences – both positive and negative – that we accumulate during life and are capable of applying to our work. When we move away from the familiar, possibilities that we might never have even imagined start to emerge.

That’s what happened for me after I left The Content Mill. Among other things, I have drawn upon skills acquired at that job – working with WordPress, for example, the online blogging and content management system. I used them to build my author’s website (I had bought the domain name a dozen years earlier) and launch the blog that you are now reading.

Here are strategies of six other women, representing four different generations, who have applied their human capital to find purpose and meaning without a job.

Laura E. Kelly

Write your own story. As Global Editor-in-Chief at Reader’s Digest books, Laura E. Kelly, 57, worked with bestselling authors like Mary Higgins Clark, James Patterson and Walter Isaacson. But when the company, and the book publishing industry, began to implode, she was assigned to whittle down her staff while still producing 50 books a year.

Kelly’s virtuosity with words and images, honed during years as a magazine editor, became less important than Excel spreadsheets and human resources meetings. After 5 years of misery and 25 of being a good corporate soldier, “I whittled down my corporate staff once more – this time by deleting my own position from the top of my org chart,” she says.

That was nine years ago. The plan, at the beginning of what we now know as the Great Recession, was to help her husband, the writer Warren Berger, launch his first book, Glimmer: How Design Can Transform Your Business, Your Life, and Maybe Even the World. It was the start of a business, in which they work together, to help creative solopreneurs (among them writers, painters, photographers and actors) promote their brands online.

To build her digital skills, Kelly took advantage of all the free tools then emerging, such as: WordPress, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Inkscape, Tumblr, iMovie and Keynote. When, as a Reader’s Digest employee, she had tried to take her writing and design talents to the company’s growing digital division, she hit a roadblock. “Corporate life was all about silos,” she says. Without that rigid structure, “You can design your own job.”

Now that most entities have their internet and social media branding well established, Kelly is pondering what her next challenge will be. Her advice to people leaving the corporate mother ship begins with: Write yourself a short essay telling your career story. Look for themes like, “what you loved as a child and aspects you’ve loved about past jobs,” she says. “These are things you’ve gravitated toward your whole life, and probably have gotten pretty good at doing, whether or not you realize it.” This is your chance to build upon that story by trying something new, too. Scared you’re not good enough? Then summon up the old cliché, Kelly advises: “Fake it ’til you make it.”

Samantha Shaddock

Take short hops. For those who cling to the notion that we should “hang in there” at the job from hell, Samantha Shaddock, 40, offers a contrary perspective. “If you’re not happy where you are (and can’t fix the problem), leave,” she advises. “Maybe wherever you land first won’t end up being your forever job, or your forever career, but you’re certain to learn something valuable wherever you go.”

We met when Shaddock was home page editor at The Content Mill, having come onboard at about the same time, and she quickly caught my eye as a crackerjack headline writer. Management noticed it, too, and corralled her into leading in-house seminars on how to write headlines for search-engine optimization. While making smart editorial decisions, Shaddock also exercised extreme diplomacy as reporters and editors jockeyed for play on the home page.

Within a year, though, other opportunities and family needs beckoned. She moved back to Dallas to juggle it all, landing a job at The Dallas Morning News, where she had previously worked straight out of college. By then a seasoned journalist and SEO expert, Shaddock was rehired in part to help the newspaper develop its social media strategy – a great way to leverage the digital chops she had developed in New York. But the purchase of her first house led her to seek extra work to offset new expenses. And that, in turn, led to a full-time offer that seemed too good to refuse: a senior marketing editor position at a software company. Was she leaving journalism, I wondered?

Not so fast. The new challenges invigorated her, the work environment less so. But again there was a positive takeaway: It put her in an entrepreneurial spirit. “I realized that if I struck out on my own as a consultant, I could sidestep much of the process and hierarchy that I’d seen muck up the works at larger corporations,” Shaddock says. She left to launch what would become two ventures of her own. One was her consulting firm, The Shaddock Agency, providing social media, digital strategy, copywriting and design services – all skills she had picked up in each of her prior positions.

Meanwhile, missing the camaraderie and sense of purpose of a newsroom, and with few opportunities in Dallas to return to journalism, Shaddock created her own publication. She called it Gutsy Broads, and designed a logo of a woman in a tutu shooting a bow and arrow. “It’s a symbol of women focusing on what they really want for themselves —in their careers, personal lives and otherwise — and then shooting for them,”she says. Running the website, which celebrates and encourages smart risk-taking by women, “scratches a number of itches,” she adds: “writing and editing stories; designing my own visuals; growing an audience; and, most important, helping other women.”

Far from the corporate hierarchy, Shaddock devotes most of her time to working for a boutique editorial agency that started out as a client. She is able to do this work from the comfort of her home office, and still be available to her family. And Gutsy Broads is going strong, with nearly 36,000 Facebook followers and a roster of paid contributors.

Shaddock recently added a podcast – “The Gutsy Broadcast” – to her mix of written news, features and profiles. And scrappy broad (her words, not mine) that she is, she says she found the perfect place to record it: in her closet, surrounded by old work outfits.

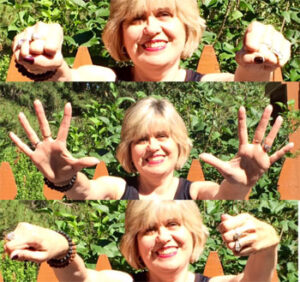

Patricia Tavis demonstrates yoga for hands.

Transform an avocation into an occupation. “By age 61 I think we all have quite a story to tell,” says Patricia Tavis, and hers has taken many turns. In what she describes as a “previous life,” she was a single mother who worked as a secretary – first at a nuclear power plant, and then for two different law firms. After remarrying, she had the financial freedom to go back to college – a “lifelong dream.” She got her associate’s degree in 1993 from Thomas Edison State College, in Trenton, N.J. Meanwhile, the arrival of three more children, two with cognitive or behavioral issues, presented new challenges, and for more than a decade that was her primary focus.

“Yoga helped save my sanity when I was trying to deal with the complicated issues involved in raising my children,” Tavis says. And when it was time to go back to work, in 2009, she leveraged it into a new occupation. She completed a 200-hour training program, became certified as a yoga teacher and founded Serene Spirit Yoga, a company based in Howell, N.J. Her specialties are chair yoga, for people who can’t get down on the floor, gentle yoga (as opposed to a more vigorous flow yoga) and special-needs yoga.

Though less strenuous, these forms of yoga still build flexibility and provide relaxation, Tavis says. Being a “traveling yoga teacher” not only avoids the overhead associated with a studio, but also enables her to bring yoga to people who are not mobile enough to get there. She teaches about ten classes per week, mostly to disabled young adults or senior citizens.

“I became a yoga teacher at age 52 in an attempt to soften the effects of aging and to teach others to do the same,” Tavis says. “There’s a reason yoga is called the fitness fountain of youth!”

Lorrie Foster

Leverage contacts and experience. One advantage of working for yourself is that you don’t need someone else’s permission to try something new. All it takes is a first client or customer, as Lorrie Foster, 61, discovered.

In a work life spanning three decades, Foster was more accustomed to managing a large team – and budget – in big organizations. That had been her career trajectory, in the corporate, government and private sectors. But everything changed with the arrival of a new CEO at the business membership organization where she had worked for 13 years, overseeing several different departments. “Early on he announced that he wanted his senior team to tell him exactly what we thought – and not to just validate his ideas. I took him at his word,” she says. “Before long I found myself no longer leading the most profitable unit and largest team, but in a department of one. I dreaded going to work. It was time to leave.”

During past jobs, and especially in the latest one, Foster had worked with high-level executives at large companies around the world. And those contacts, many of whom sit on corporate and non-profit boards, were key to her transition. Though initially she sought to replicate her experience, as an executive director or vice president, she soon found that there was much more demand for her skills as a consultant. Before long she had been recruited, by someone she met at a conference, to help corporations develop or refine their global employee volunteer programs.

One of her main assignments since then has been for a non-profit that advocates for global volunteering – most recently in response to various natural disasters such as the Nepal earthquake and the refugee crisis in Europe. Her role is to help forge partnerships between local relief efforts and corporations worldwide that want to offer financial assistance or send corporate volunteers on leave from their desk jobs.

In this capacity she has traveled to Geneva to convene a group of companies and humanitarian organizations; to Berlin to discuss the refugee crisis; and to a meeting in Mexico City of volunteers from 53 different countries.

“Through my prior work I had been exposed to corporate social responsibility, including philanthropy and employee volunteering,” Foster says. “My favorite kind of work has always been global, and I have long been passionate about both improving communities around the world and personally experiencing different cultures. Now I love what I do, and where I do it – all over the world.”

Gail M. Edwards

Retrain, retool, regroup. During the early 1960s Gail M. Edwards, 76, majored in geology at the University of Rochester, and her career path since then inspires analogies to rock formations: Again and again, she has layered skills and experiences as her work took on new shapes. Today she is an artist in Boulder, Colo., combining early passions for drawing, hiking and rock collecting.

She had started out as an earth science teacher, took time off to raise a family and reentered the workforce when she was in her early 40s. To do that, she parlayed her artistic talent and powerful sense of empathy into a new career: art therapist. And in various jobs for the Army and the Navy departments of psychiatry, she worked with veterans, children and HIV patients (she made a video of their artwork set to music). Along the way she divorced husband No. 1, reunited with her first love, and married him at the age of 51.

Edwards says that being a lifelong learner has been key to making transitions at every age. When her children were young, she studied watercolor. It took three years to earn a master’s in art therapy, as she juggled weekend and evening courses at George Washington University with child-care responsibilities. (She was living in Washington, D.C. at the time.)

During almost six decades as an artist, Edwards has continually challenged herself to learn new techniques. Her early work, in oil and watercolor, was realistic. Now it is characterized by a more abstract style, combining paint with collage. A watercolor titled Prairie Sunset, in purple and olive hues, captures a Colorado vista. After being displayed in a recent show of 30 of her works, at the Denver Athletic Club, it was chosen for an exhibit of Boulder’s Open Space and Mountain Parks.

Another recent work, Moab Arches (see the photo at the top of this post), was just purchased by a private collector and is an example of her encaustics. These melted wax paintings are an art form she began studying after the death of her second husband ten years ago. Care instructions can be found on her website: “All encaustics benefit from polishing with a soft cloth every few months,” she writes. That advice also seems apt for those of us who want to enhance our skill sets.

Alexandra Talty

Embrace uncertainty. A few days before I resigned from The Content Mill, I had coffee with Alexandra Talty, 29. It had been a long time since I had left a job, and I told her I was unsure about what to say in a scheduled meeting with my boss. “When the moment comes, you will find the words,” she said. It turned out to be great advice – and very much a reflection of her own approach.

Talty was 24 years old when she quit her public relations job at a media company and announced that she was moving to Beirut, Lebanon to become a freelance journalist. Although she had studied fiction at New York University, she had no training or experience as a reporter and was plunging into a political hot zone.

Behind the scenes, though, she had spent two years preparing. She studied Arabic; put aside a small nest egg that was enough to cover six months of expenses and enable her to leave Beirut if that didn’t work out; and interviewed colleagues in their 20s about how to get started. One gave her a rundown of must-have equipment (voice recorder and a point-and-shoot camera, not too fancy). Another advised her to start a blog that would give her practice writing. Until she felt ready to launch her own, I invited her to write “postcards from Beirut” that I would publish as guest posts.

Still, Talty says, “I didn’t realize how monumental the shift would be, which, in retrospect, was likely a good thing. Instead I focused on what I could control.” And one thing led to another. Through a friend of a friend on Facebook, she landed part-time copyediting work in Beirut. Then she launched, curated and edited StepFeed, a news platform on the Middle East. And that opened the door for what turned into a one-year gig, cohosting a segment on Radio Beirut, covering news from the Arab world. By the time she moved back to the U.S., after three years, Talty’s side hustle had turned into a full-time travel-writing career.

In the course of it, she has written about her adventures sailing on a Bahamian mail boat for four days; toured Lebanon with a motorcycle gang; and offered advice about travel in dangerous places. During the past five years, her human capital has rapidly compounded, giving her perspectives and experiences that she can apply to new pursuits. None of that would have happened if she had stayed in her corporate job. “I am ecstatic that I made that leap,” she says. “If you are clear about what your next goal is, you never know who might be able to help you reach it.”

Deborah L. Jacobs, a lawyer and journalist, is the author of Four Seasons in a Day: Travel, Transitions and Letting Go of the Place We Call Home and Estate Planning Smarts: A Practical, User-Friendly, Action-Oriented Guide. Follow her on Twitter at @djworking and join her on Facebook here. You can subscribe to future blog posts via RSS feed, or by using the sign-up box on her website’s homepage.

RELATED POST

Moab Arches, By Gail M. Edwards

Moab Arches, By Gail M. Edwards

Thanks Deborah Jacobs for such a wonderful post. It could not have come at a more opportune time for me as I can relate to many points that you have brought out.

Thanks for your kind words. Hope all goes well for you. The world is full of possibilities!

Deborah,

Thanks for the blog post. I love each story of finding, or creating, a unique path through life.

I have dealt with this issue myself. In 2011 I sold the company I had founded to a tech behemoth. It was the American dream. I could do anything I wanted each day for the rest of my life.

And that was a problem.

After a year sailing the Bahamas with my wife and two kids, I came back to civilization and had to deal with the question you address in this blog post, “How will I find purpose and meaning in life?”

It took me three years, but I’ve found it. And, I was able to do so without falling back on a job or starting another company.

Cheers,

Kevin

Thanks so much for sharing your story, Kevin. This is an angle I plan to address in a future blog post. Please stay tuned!